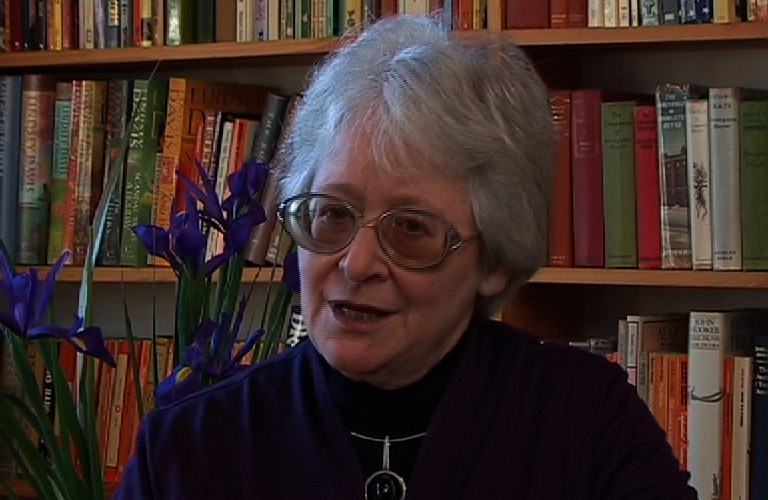

Juliet Flesch is a professional historian and librarian. She first became involved with asylum seeker issues in 2001, when she began visiting Maribyrnong Detention Centre. She was one of the first to begin visiting detention centres regularly. She continued to visit detention centres all over Australia and maintained correspondence with many detainees, including on Nauru.

More information on Dr Juliet Flesch

- Professional profile, Professional Historians Association (Victoria), Dr Juliet Flesch’s professional profile and history.

- “PM Accused of Double Standards”, The Age, 2004, a brief article on the granting of permission for a wealthy Iraqi leader’s son, Izzedin Salam, to visit his family in Iraq despite being on a protection visa. Dr Juliet Flesch is quoted.

- Letter to the Editor, The Age, 2002, on visiting Maribyrnong Detention Centre.

- Letter to the Editor, The Age, 2002, on visiting Maribyrnong Detention Centre.

Transcript of Interview

13 AUGUST 2006

Interview conducted by Kirsty Sangster

MS SANGSTER My name is Kirsty Sangster. Today’s date is 13 August 2006. I am conducting an interview with Juliet Flesch.

DR FLESCH Flesch.

MS SANGSTER Flesch. The interview is being conducted in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Could I please have your name and spelling?

DR FLESCH My name is Juliet Flesch. The surname is spelt F-l-e-s-c-h.

MS SANGSTER What was your name at birth?

DR FLESCH Juliet Flesch.

MS SANGSTER And the spelling?

DR FLESCH F-l-e-s-c-h.

MS SANGSTER Do you have any other names?

DR FLESCH My middle name is Ella.

MS SANGSTER And the spelling?

DR FLESCH E-l-l-a.

MS SANGSTER Any nicknames?

DR FLESCH No.

MS SANGSTER Birth date?

DR FLESCH 6 June 1943.

MS SANGSTER And your age?

DR FLESCH I am now 63.

MS SANGSTER The city and country of birth?

DR FLESCH I was born in Melbourne, Australia.

MS SANGSTER So how did you actually get involved in working at the detention centre?

DR FLESCH I got involved through the work that Alice Garner was doing, and actually describing it as work at that stage is probably putting it a bit too strongly. Alice was doing her PhD at the same time as I was in the History Department at Melbourne, as well as acting and being a mother and doing research work for people

MS SANGSTER And was there a specific Visitor’s Programme set up at that point or – – –

DR FLESCH I’m not sure by what you mean by that. There were specific hours at which people could visit. There was a protocol attached to the visiting but I never formed part of any organised group, it was always very much a matter of seeing who was going out that day. I don’t drive so it was always a matter of finding someone who could drive out to the Detention Centre from the university, and there’s a group of us that had been going for a long time, but Alice in fact stopped I think – well, pressure of work and pressure of having another child and a few other things like that. I’m not sure that she’s been out there at all recently, so probably going out there sort of regularly for five years I may be the longest one of that Melbourne group.

MS SANGSTER Sorry to interrupt, I think your mobile phone is on.

DR FLESCH M’mm.

MS SANGSTER Sorry, because I can – – –

DR FLESCH Sure

MS SANGSTER It’s interfering with – – –

DR FLESCH Sure.

MS SANGSTER – – – the microphone, sorry.

DR FLESCH I should have turned it off anyway.

MS SANGSTER And when you first went out there what did you see?

DR FLESCH I was absolutely shocked. You want me to describe how actually going to the Detention Centre is? Okay. Well, you drive to a car park where you are then, when you get out of the car you are confronted by fifteen foot bard fence, steel fence. On my first visit that fence was not topped by razor wire, it is now. You buzz at a gate and some – a voice asks you what you’ve come for and you say, “I have come for a visit.” You are then admitted to a much wider yard and in the middle of that yard there is a sort of building

MS SANGSTER So they are actually physically – – –

DR FLESCH They’re physically patted down both when they come to see and when they go back.

MS SANGSTER And on that first visit who did you meet?

DR FLESCH Okay. At that time the visits rules were that each visitor could call out up to four detainees, so if there were three of you you could get twelve people out. The catch is you had to know the name of the detainees. That by the way was very funny because at one stage I wasn’t sure how somebody spelt his family name, and I may say knowing how somebody spells Mohamed can be pretty funny when you realise there are Mohameds and Muhameds and Mahamads and all the variation, and one of the officers who is a particularly unpleasant and I think unsuitable woman for the job gave me a very hard time, you call these people your friends and you can’t spell their names and I said you’d be astonished at the number of people who can’t spell my name, but now I think we’d kind of decided that I wasn’t going to give you the names of the people that I was going to see, but the first group that I met were a Pakistani who is now on a permanent visa

MS SANGSTER And after – after that first visit did you – you then set up to meet one of these people regularly or – – –

DR FLESCH We went – we – the three of us, it was Alice and one other person and I – look we came out of that in tears. I can’t begin to express how shocking I found it and I hope we are going to talk about that later. And, yes, it’s always seemed to me inexcusable just to make one visit and this is something that I used to get into arguments with students and fellow post grads who would get in touch with me and say, “I feel I need to find out about this, I would like to go out with you.” I’d always said I won’t take anybody who is not prepared to make a commitment to – as a rule of thumb I’d say at least four visits. I said you can’t get somebody out, get them to tell you their story which is something they – the first visit is always traumatic both for the visitor and for the person being visited and they are not people in a zoo. I mean to me saying I need to go out and see it is about equivalent to the eighteenth century business of going to bedlam to look at the mad people on a Sunday afternoon, you know, it’s just – it’s not on.

MS SANGSTER So it’s a bit of a (indistinct).

DR FLESCH So we – I’m sorry – we felt that it was just not on to go there once and we went several – we made a commitment that we would go at least once a week and that became difficult because Alice couldn’t always make herself free. I mean, as I say, she had many, many other commitments, so we looked around for other people who would be able to help with the chauffeuring. So it became a sort of moveable group, but really there was always – there were always people who, you know, had been there before and, you know, who therefore could call people out as friends and it does change the dynamic of the meeting a great deal because you’re not constantly making people relive the trauma of why they’d actually come to Australia.

MS SANGSTER So in that first visit where did some of the sort of shocking – shockingness of it lie?

DR FLESCH The – the stories of the people who arrived, two of the people that I saw and actually I will name them because their cases have been in the newspapers and they have both got permanent visas now

MS SANGSTER And did you know what to say in response to that?

DR FLESCH No. It was dreadful. All I kept saying was I am ashamed, I apologise for my country, you know, which is rubbish and I mean looking back on it now I’m amazed at their forbearance, they must have got so sick of Australians coming in and saying I’m sorry for my country because the answer is, well why the hell don’t you go and do something about it. Now, you know, after a while when you developed better relations with them you could actually say, well, we are doing our best, we are doing what we can, you know, but – and we could discuss the political situation a bit more, but at the time, you know, all you could say was, “Can I bring you some cigarettes, would you like a phone card?”

MS SANGSTER So there was a sense of helplessness?

DR FLESCH Total helplessness, yes, and total rage, and at that stage there were a lot of people who really didn’t want to know. I mean I found it quite extraordinary and it’s been one of the most distressing things of my whole involvement with this is the number of long standing, and I mean, I’m talking about 30, 40 year friends that I have lost over this because I really felt at the stage when – and I probably became a total bore about it but, you know, the people finally said “Look can we talk about something else” I’d understand it, but the ones who just said “I don’t care” and there were – you know, there was one of my Canberra friends who said casually, “Look Juliet I’ve got to tell you, my withers are totally un-rung by this.” I said I can’t believe it, all the ones who said, well I have got to tell you, I agree with what the government is doing, and that’s the point where it was just – to me it’s like somebody saying, “Look, I’m in favour of child molestation.” You know, you might – you might remember the good times you had for 30 years but your relationship is changed forever.

MS SANGSTER So the whole – – –

DR FLESCH Yeah.

MS SANGSTER And when – at that first interview again what was the environment of – where were you actually sitting?

DR FLESCH Right, okay. I’m finding it very difficult, Kirsty, to keep concentrating on that first interview.

MS SANGSTER Yes, sure.

DR FLESCH Don’t forget it was over five years ago so, you know, I – there’s a certain amount that has changed over the time. But anyway, okay, that very first interview you were let into a sort of fairly dingy sort of waiting room thing that had sort of plastic chairs and a few tables but there was – there’s a – outside you could walk out into a courtyard which was paved which had 15 foot complete brick walls so that you could see nothing. I mean you could look up and see the sky but you could see nothing of the outside world at all. In the courtyard there were one or two very depressed looking pot plants which obviously nobody was in charge of watering and there were some chairs fixed to the outer perimeter walls and – although you weren’t supposed to take furniture out into the courtyard we all used to pick up plastic chairs from the inside visit’s area and take them out so that we could sit in a group. You were under constant visual surveillance from the – the guards, who would occasionally come out and smoke because that of course was where you went. We went there because it was, well it was February, it was very hot, but also the guards were all smokers so it was just easier there and sometimes you could try and shield them a bit from the visual surveillance. I mean not that anything in particular went on but, you know – and you felt that sometimes if you did drop your voice that perhaps people wouldn’t hear every single word that was going on.

MS SANGSTER So after that time you decided that you would visit regularly?

DR FLESCH Well, I don’t think we ever made the decision that we would visit regularly but we certainly didn’t feel that – we couldn’t just go and say God, isn’t that awful and forget about it.

MS SANGSTER Right.

DR FLESCH We felt – we felt that these people were human beings who had gone to some trouble to tell us something and we couldn’t just – well again it wasn’t about us, they needed support.

MS SANGSTER So then did you – how did that work, so you just would try and get a lift out every week?

DR FLESCH Yeah. Yeah, well generally on the way out of the detention centre we’d be saying, well I can do it next Thursday, can you, you know, and there’d be that sort of discussion because it represented either a whole morning or a whole afternoon basically. The visiting hours – the visiting hours changed all the time but at that stage you could get there from, I think it was 10 o’clock to 12 o’clock and then you could go from one o’clock to five o’clock and then seven o’clock to nine o’clock or something and they’ve changed that now, but there was sort of three blocks that you could go in, and it was quite interesting over time that you found you got a very different vibe if you went at different times of the day. I used to prefer the mornings although I’ve got to say the guys didn’t particularly because they tend to sleep so badly that they tended to be asleep at ten o’clock in the morning, but there’s – there’s a limit on the number of people they will allow in as visitors at any one time, and the guards used to make – used to take particular pleasure in strutting in and saying, “Anybody who’s not family will have to leave now because there are family members wanting to come in”, and I mean for men or women who have arrived completely without family, who’s entire family is in another country, it was the cruellest of things to say, so, you know, I used to make a special point, I remember doing it once with one of the African guys announcing brightly, “I’m his sister” – you know, just staying there. I mean this is a boy who is perhaps young enough to be my grandson, and the guard being absolutely furious and, well you’re going to have to leave anyway. So the afternoons tended to get pretty crowded and the evenings again were very much more crowded because of course for anybody who had a full-time job that was the only time they could visit, so if I’d lived in the vicinity and driven there it wouldn’t have mattered so much, but given the fact that we made such – it was such a coordination effort to get there the morning was when we chose to go.

MS SANGSTER And were you visiting the same people after that point?

DR FLESCH Well, at that very – during the first period, and it’s important to remember that the detention centre population fluctuated a great deal – now – well, not the detention centre population, there were always a lot of people there because that was another of the things that I found most shocking and I continue to find very shocking that the Immigration Detention Centres contain convicted criminals convicted of really serious crimes. I mean these are people who’ve committed a crime that attracted a gaol sentence of over 12 months, so we’re not talking about parking offences here. Those criminals who are awaiting deportation are put in with the men, women and children who have fled persecution and – sorry I’ve lost track of where I was,

MS SANGSTER That the people that you were – – –

DR FLESCH Did I go and see the same people

MS SANGSTER And were you actually allowed to spend as long as you wanted there or was it only – – –

DR FLESCH No, they were – the visits hours were very strict.

MS SANGSTER Yes.

DR FLESCH And you were booted out.

MS SANGSTER Yes. Or if the guards said that the family members were coming in also later?

DR FLESCH Yes. Yeah.

MS SANGSTER And you were saying that the men often slept badly. Was that – would they talk to you about those personal things?

DR FLESCH Yes, they would if we asked, but I mean it was perfectly obvious, I mean most – most of the asylum seekers, and this is one of the things that I find also truly shocking, is the fact that people, the people who came to Australia seeking asylum were on the whole young, pretty healthy, extremely brave and very resilient to people. I mean these were people who had resisted intimidation, persecution in their own country and I really feel free to say this because most of them have now of course been accepted as refugees, which means that by International criteria they are deemed to have had a well founded fear of persecution. So, most of them had been politically active and had resisted it. Now, they were on the whole resilient, optimistic, very brave people, and by the time they had been in detention for six to 12 months they were drug dependant because they were being given tranquillisers, sleeping pills, whatever, the medication of people in the detention centres is an absolute scandal. They were depressed and therefore being given Prozac for – well, whatever, for the depression. They – if they went on hunger strike for any length of time which many, many, many of them did, their teeth start rotting and they do not seek dental treatment because they would be taken from the detention centre to the dentist in handcuffs, and one of them, and this was last year, described to me being taken into the dental surgery in handcuffs and having the dental nurse back away from him, and he was horrified. I mean he’s a man in his 40s who was – he was a public servant in Iran, you know, not somebody who’s used to being a terrorising figure, and he was just so horrified he just said to the dentist, “I’m not doing this” and got up and went. Now, you know, he actually needed dental treatment, so what happens is that we take these healthy individuals and they are reduced to shaking wrecks. Now do they talk about the fact that they are not sleeping

MS SANGSTER And sometimes when you went there and you called out a name was that person – had that person been moved or did you find that – – –

DR FLESCH Yes. Yes. We had several interesting things. I mean the curious thing is they’ll just say that so and so is not available. And you say, “Do you mean they’re asleep?” “No.” And they finally say, “He’s not on site”, and this was particularly interesting for example when there was a woman who was brought down from Nauru to have a baby and when – she was brought down because she was in fact a doctor and she knew that she was in trouble and it was interesting because they brought her husband down as well and I always thought that was because they thought she might die and they wanted to be able to hand the baby over to someone because otherwise they very frequently sent family members leaving other family members still on Nauru. But anyway I was told, now this woman was not on site, and we said, “Do you mean she’s had the baby?” And then, “That’s – we’re not at liberty to comment on that, it’s a privacy matter.” And the only way we could get any idea of whether this woman had had her baby was by saying, okay, somebody had to go back out through all the security thing and put her husband’s name down and then we were told, no, he wasn’t there either and we thought, okay, you know, they can’t have been sent back to Nauru yet so she must be having the baby. But then there was one time when we went in to see a particular guy and we were just told, “Oh no he’s not here anymore.” “Where is he?” And finally, you know, when somebody finally said, “Okay, look, if you’re not going to tell us where he is I’m going to ring his lawyer.” They finally said triumphantly, “Well his lawyers are going to have to go to Port Hedland to see him.” So he’d been moved back to Port Hedland and they hadn’t bothered to tell his fiancé and he hadn’t been able to tell his fiancé. The interesting thing was that when we got in to see the other detainees that day we were told, “Oh no, Arthur’s still here, he’s just been held in isolation. He’s not leaving for Port Hedland till this afternoon.” So, there was actually no reason why they could not have allowed just one of us to go and see him in the isolation unit to say goodbye. You know, it is a deliberate thing to disrupt any support network those people have.

MS SANGSTER So there was an – there is an actual isolation unit?

DR FLESCH Oh yes. Yes. Well, it’s variously called the Management Unit, the Isolation Unit. In Port Hedland to my absolute rage it was called Juliet Block. I used to – when I used to ring my friend in Port Hedland and I would say, you know, I want to speak to so and so, this is Juliet, I’d say Juliet and they’d say, “Yes, like the punishment block.” It was dreadful. But, yeah, there’s an isolation unit and it’s in Maribyrnong and I have to stress to you that Maribyrnong is sort of 5 star accommodation compared to the other detention centres, compared to Baxter, compared to Woomera and Curtain which were after all closed down as not being fit for human habitation, and Baxter which was purpose-built as a detention facility, and I think frankly when we finally got rid of all the refugees is going to be used as a prison. That’s my private belief. You know, it’s actually a state of the art prison. Port Hedland also had appalling facilities. Maribyrnong has an isolation area which I – of course you never, no visitor ever gets to see where the detainees are actually held, but if somebody behaves inappropriately they can be put in the isolation area, but sometimes visitors are allowed to see people who are in the isolation area and they’re brought to separate interview rooms, so they’re not allowed into the visiting area with other people, but you can go in. I remember thinking this was absolutely extraordinary, because when I went to visit my friend Alan when he was being held in the isolation area, I was visiting with one of my cousin’s daughters and her 8 month old son, and Kylie and Thomas were an enormous hit with the detainees because apart from anything else Thomas was just gorgeous and he – we went in there and we were ushered into a basically sort of interview room with a view of the prison yard but, you know, it was furnished with a desk and three chairs and absolutely nothing else, you know, not a picture on the walls, nothing, I mean just sort of grey, and we went in there and I remember saying to the Centre Manager afterwards that I am sure it really did 8 month old Thomas a lot of good to be in (indistinct) to visit in that area because normally he used to have a ball that he used to kick around and Arthur used to kick it with him but, you know, of course they couldn’t do that in the isolation area.

MS SANGSTER What sort of reasons were people kept in isolation?

DR FLESCH Ah, very interesting, interesting and varied. This particular person was being held in the isolation area because he had an injury to his foot and one of his visitors had noticed that the bandage which had been put on by a doctor was getting very dirty so she brought him a replacement bandage and she told him that she was going to do that and he was, you know, grateful for it, so when she got into the visiting area he said, “Where’s the bandage?” and she said, “I wasn’t allowed to bring it in because it is a medical supply and we’re not allowed to do that.” Now this guy who had been in detention for a very long time and had an absolutely horrific story not only of his reasons for leaving his home country but also a quite horrific time of being bashed in the detention centre. He’d been in several detention centres and he had been bashed, he had been traumatised in various ways. On this particular occasion he just lost it and he flung a chair through one of the windows and I mean he was immediately overpowered, taken off to the – I mean – and I mean nothing excuses it, he – okay he lost his temper, but I mean all one can say is that like any civilized person he took out his rage on an inanimate object rather than on another human being, but he was then held in the isolation unit for a very considerable time, but because he was known to be so severely traumatised and so severely depressed I don’t think the detention centre management dared to actually keep him – they said he had to be isolated from the others because he was a threat and violent and all the rest of this nonsense, but I don’t think they dared to deprive him of visitors because I think they were seriously frightened that he might kill himself. One of the things that’s become abundantly clear to me about the attitude towards asylum seekers in detention is that anything they do to themselves short of killing themselves is fine by the Department of Immigration and the Detention Centre staff. They really, really don’t like deaths in custody, but anything short of that, who cares.

MS SANGSTER So self harm is something that’s quite common?

DR FLESCH Well, Amanda Sandstone doesn’t get too worried about people on hunger strike and Philip Ruddock seemed to be more interested in accusing detainees of sowing their children’s lips together than of wondering why they might do that, and certainly there was a case that was very widely publicised in the Australian newspapers about a detainee on Nauru who has since been given a permanent visa as a refugee, he had lost the sight of one eye and a leg when he was in Afghanistan, he was – he objected to the Taliban practise of selling women and he – he’s actually a Pashto not a Hazaro which makes him remarkable among the Afghan asylum seekers, because most of the Afghan refugees are Hazaro and the Hazaro have been persecuted in Afghanistan for hundreds of years whereas the Pashto – I mean as I understand it Hamad Kasi(?) is a Pashto, Pashtun – anyway this guy had objected to the Taliban selling women and children and they lobbed a hand grenade into his shop and blew him up and he lost an eye and a leg, and he not unreasonably – well he didn’t leave Afghanistan at that time, he went on fighting for women and the Taliban killed his little brother who was 8 years old and at that point he left Afghanistan, but he had a stump and a prosthesis when he got onto Nauru. The prosthesis which had been very badly damaged caused his leg to ulcerate and he got to the stage where he had to be carried everywhere, you know, which was just horrific, and people started agitating in Australia to say this man has to be brought to the mainland for medical treatment and in fact I seem to recall that even Kieren Keke, the Minister for Health on Nauru, was saying this man should be brought for medical treatment, we can’t deal with him here, and Amanda Vanstone delivered herself of the opinion that there was no need for him to come to Melbourne because ulcers were not a terminal condition and presumably a few of the Changi survivors had a bit of a talk to her because he was brought to Melbourne. I still remember that was one of the most amazing moments when I went into the – I’d been writing to this guy for some time when he was on Nauru, but I didn’t realise that he was coming to Australia because of course you never get told any of that, it’s always a surprise when people are moved, it’s so quiet, without you knowing about it, but – so I’d gone in to see somebody else and suddenly this guy comes out, one eye, one leg, and I thought that’s got to be him, so I went over and said, “Hello, I’m Juliet” and greeted each other with, you know, great cries of joy and doing my sort of lady bountiful thing I said, “Look you’re obviously here to see somebody else”, because somebody else had called him out, and there is an etiquette you don’t mix somebody else’s refugees at work. So I said, “I’ll leave you to talk to whoever it is, but is there something I can bring you next time I come”, and I thought, you know, cigarettes, phone cards, whatever, and he said, “Lawyer.” That’s particular – as it happened I could say it’s all right your lawyer’s organised, you know, you’ve got a lawyer, because I mean that was the first thing you did for everybody, but this is particularly relevant when you look at what’s being suggested now about warehousing people on Nauru. Amanda Vanstone keeps saying they will have access to full legal recourse. Well, she can’t guarantee that. Nauru is a sovereign country. She can’t guarantee that anymore than she could guarantee it in Guantanamo Bay. So it’s – it’s just a complete lie and so for the people who came from Nauru the first thing they wanted was a lawyer because they knew they were there by an Australian Government behest and they needed an Australian lawyer.

MS SANGSTER And were there particular people that you sort of developed closer friendships with?

DR FLESCH Oh yes. Now I’m going to rephrase that very carefully because a great many people who visit the people in detention centre develop very close relationships. There have been marriages, there have been – there have been very successful marriages, there have been some very unsuccessful marriages and there have been some spectacularly unsuccessful affairs. And I make it clear that my relationship with the detainees, I think there are – there must be some where I’d have to have been a very young mother to have been their mothers, but I am very conscious they are all younger than I am, they are friends and – but, yes, you do develop friendships with them and one of – in a funny way one of the most difficult things to deal with is that you actually – you don’t have to like them all very much. When while you are visiting in the detention centre to me it’s actually – whether you like them or not is not important, it’s almost like being a teacher, you know, whether you like the kids in your class or not is not important, you know, you are there to do a particular job as it were. Certainly there are some that are easier to talk to than others and the real difficulty is if you find somebody who’s got really good English and you actually don’t like them that’s a real bummer because it’s much easier if they’ve got good English and you do like them. I have developed I would say close friendships with some of the people that I visited, but the other thing that I think is equally important is that you do in fact have to recognise that they may not like you, I mean that’s one thing, but also for a lot of people the last thing they want to do is to find themselves for the rest of their lives as refugees. Now, I am very conscious of this because my parents came to Australia in 1940 and for the rest of their lives they were referred to as New Australians and my mother particularly used to get outraged about that. She would say, “I was Australian before you born” – you know, she having made a conscious decision to become an Australian she did not want for the rest of her life to be defined as a migrant. And I think a lot of the refugees when they come out they, if they can form other bonds, now I’m thinking particularly for example there was a Kurdish Turkish couple who came to the detention centre and I got on very well with them, they were lovely people, and we sort of rang each other up a couple of times after they came out of detention, but they – they’ve got their TPVs, I hope they’re going to have permanent visas- they have as it were disappeared into the Turkish community. They – they know people there. There was another young man, I went to his wedding who is – he was – he’s an Iraqi, but his brother is out here, he is an Iraqi Christian, he’s in a sort of a church community, he’s married within that community. I don’t think he wants to keep in touch, and I don’t blame him. In some ways for many of them I just remind them of a particularly nasty part of their lives. So you can form close friendships and you can form friendships that seem to be very close while the people are in detention and once they’re out they’re not – that said by the way I am absolutely certain that if I rang one of those people up and said, “I need help” I do not believe there is a single one of them who’d be too busy.

MS SANGSTER What about some of the other conditions in the detention centre? You were talking about the medical care.

DR FLESCH Yeah.

MS SANGSTER There was – what about women who for example are pregnant?

DR FLESCH Ah, well, I told you about the woman who was brought down from Nauru. There was another case of – now I have to be clear about this young woman, she was not in fact a refugee. She was a student who had been sent from Vietnam to an English college here. Now she’d – she dropped out of the course, she’d gone off grape picking and developed a boyfriend and – now the boyfriend was Vietnamese, I don’t know whether he was here legally or not, but when she got pregnant he didn’t want to know. And she – I don’t even, I can’t even remember how she got picked up, but she was desperate not to be sent back because it was quite obvious that her family were going to be absolutely furious with her because she was just going to be bringing back another mouth to feed. I mean it was going to be awful. And I remember having a long talk to her about possibly having the baby adopted and all the rest of it, but anyway she didn’t and she has taken the baby back to Vietnam. Now, I met the mothercraft nurse coming out of the detention centre one day when I was going in to visit her and the nurse was absolutely shaking with fury, because she had gone in to do a postnatal examination of this young woman and had been obliged to do it on the floor in the isolation room because there was absolutely no provision for that. By the way, that reminded me of something in the isolation room, people were put into the isolation room also if they had some sort of medical condition which didn’t require hospitalisation and there’s one of my friends who was catastrophically burnt in the detention centre and he had to wear a full pressure suit and he was held in the isolation area at night and the thing that horrified him was that he was locked in and he tried banging on the door because he wanted to get out to the lavatory one night and there was just nobody there, and he was terrified, and he used to talk about the fact that his pressure suit, he had one that he wore and one that he washed, I mean and – I mean this is an absolutely vital thing, not only because of the pressure thing, it’s also to keep out infection, and he said the detention centre manager used to particularly enjoy coming into the room where this thing would be hanging because of course there was nowhere to hang it, he’d have it hanging on the end of bed, and the guy would say “That’s pretty untidy” and throw it to the floor, thus making it dirty, and this poor guy who’s terrified of dying from infection from his burns, you know, would be left just devastated. What was he supposed to do, wear the other suit for two days? Dreadful.

MS SANGSTER So he was actually kept in the isolation – – –

DR FLESCH During the night, yes and I don’t know how long that went on for. It may only have been a few nights, because he was in the general area when I saw him, but he’s told me about this since.

MS SANGSTER So the sort of staff that you were confronted with when you went in you felt lacked any proper training?

DR FLESCH Well they certainly don’t have any training and in fact there were quite obviously – there would be some very short term staff who would be – I mean they got some sort of on the job training, but I mean as in long term training specifically for this – I think you’ve got kids who were sent by Centrelink, frankly, you know, they would tend to last a very short time, but I mean presumably if you’re on one of those work obligation things where you have to go on applying for so many jobs a fortnight, if you’re told put on a uniform and take yourself off to the detention centre, I mean I don’t know whether you can say no. Now, many of the staff had come from the prison system. Don’t forget the company that manages the detention centres used to be called Australasian Correctional Management. Now, you might want to think exactly what we were trying to correct in refugees. We may well be saying correct the illusion that Australia has some sort of respect for International Human Rights law but, you know, why should they have been corrected for anything. Many of them had come through the prison system and that had its pluses and minuses, because some of them had a very clear idea of prisoners rights, and, you know, there’s been quite a development in prisoners rights, but then there were others who frankly I think they were just power hungry maniacs. So, yeah, and then there were some very decent people. I remember one of the detainees saying to me once, we were talking about a new guard, and he said, “Oh yes, yes, he is still clean boy, he has not yet become dirty.” I thought that’s interesting and I wondered how long that kid was going to last and he didn’t last long. Now we also heard an amazing story of one guy who’d come through the – he had been a prison officer for a long time and he – he was quite well respected but the detainees have a theory, and I will tell you this is a theory because I have no reason to believe that it was true, but they believed that he worked for the CIA. Now, I actually think this is pretty funny, but anyway, sorry. He used to go on holidays to America and they all said that’s because he’s going to report back, but he was taking one of the detainees to a medical appointment in the city and on the way back the – he knew how much the detainee really, really resented being put in handcuffs and the other, because there are always two officers accompanying one detainee, this is our taxes at work, the officer said, “We better put the handcuffs on”, and this guy said, “Oh no, for heavens sake”, and he was dismissed. Sacked for not putting the handcuffs on, so, you know the – they vary enormously these people.

MS SANGSTER You were saying earlier that they referred to you as Care Bears?

DR FLESCH Yes.

MS SANGSTER Was that in a derisive sort of – – –

DR FLESCH Oh yes. Yes. I mean they – look, okay let’s do a real bit of class stuff here – a great many, and certainly the group of people that I went with, but a great many of people who visit the detention centre are, if they’re not relatives of the people being detained, and I’m not talking about the people who are visiting the prisoners about to be – former prisoners about to be deported, the refugees – people who are visiting the refugees are overwhelmingly middle class, they are I would say overwhelmingly female and that’s got to do with the amount of spare time that middle-aged ladies have got, and yeah, we were better educated, better spoken than the guards and many of them resent that. There’s a definite resentment there. There’s also, look it’s a bit like visiting a hospital, you’re just interrupting a routine, aren’t you. I mean it’s a real nuisance. You’ve got to go and let people in and let them out and do that sort of stuff and put up with them whinging because the coffee machine is on the blink, and there was a – but there’s a real, how can I put it, I think many of the guards simply do not realise that they are dealing with people who are utterly innocent of anything. And don’t forget if you’re constantly being warned that these people are illegally here, that they’re rich people who can pay people smugglers, that they could be terrorists, you know, you will adopt a certain wariness towards them and your attitude towards people who insist on treating them like normal human beings may be one of resentment.

MS SANGSTER What sort of services did the government provide inmates?

DR FLESCH Ah, well they got meals which were supposedly culturally appropriate. Can I say that a great deal of what I used to take into the detention centre was food stuffs. But they provide meals, they provide – well, accommodation as in sleeping accommodation. The Brigandines regularly used to bring in more blankets because there were regular complaints about the heating and people were freezing. The accommodation by the way can be up to six people in a room which can be two lots of bunks and then two beds on the floor in the rooms. In the family area there, women and families are housed in a different sort of wing at the detention centre. Now I can’t – you’d need to talk to one of the inmates about this because I don’t know what the architecture of the detention centre is, but they were in a different wing and there was at one stage an Iranian family of mother, father, two mid teenage girls and two boys aged I think 13 or 14 and 8 and they were all in one room for a considerable time as in, I mean, months. If you think what that does to family relations, it’s disgraceful. It’s something we would not tolerate for one minute for an Australian family. And by the way it’s very common for the Minister to say, “Oh well it’s much better accommodation than they’d have at home.” Well, I’ve got to say no, we were talking about a middle class family, in fact the father had been the personnel manager for a large international company in Iran, so, yeah, they were not used to all living in one room frankly and it was pretty horrific. The other services provided, there is a nurse who is allegedly on duty all the time. Now she actually is not. There is a counsellor. Now the turnover in counsellors seem to me to be quite extraordinary and I think that is because, well I would have to say I don’t believe any social worker worth his or her salt would work in a place like that. I mean they just – it’s a horrific environment. The English teaching is voluntary and happens generally on a daily basis. Now everybody speaks very highly of the English teachers on a personal level, you know, “Fiona, she is a lovely lady”, you know, that sort of comment, but the extent to which the teaching is actually helpful is very debateable because it’s not structured to the individual student in any way. In fact one of the students said to me, because I used to go there in the mornings I was very conscious that I was actual taking them away from their English classes and I used to say, “I’m taking you away from your English class”, and he said, “Oh but talking to you is much more useful because I already know how to say, ‘My name is Charlie’ and ‘Today is Tuesday'”, because the population was constantly changing and it’s not just the refugees of course who get the English tuition, it was anybody who happened to be in the detention centre, so you would have Vietnamese visa over-stayers who were waiting to be deported who would come to the English classes and, you know, they had been taught how to say, “My name is Charlie, today is Tuesday” yet again. So, in terms of other services there’s some gym equipment. They – there was an enormous fight which you might remember about the Maribyrnong Detention Centre in, I think it was 2002, it may have been 2001, about access to the grassy area. Now, the grassy area was exactly what it sounded like, you know, a bit of the – within that 15 foot perimeter fence, and – but the point is it’s sort of harder to watch people playing a soccer game to be quite sure that you know what they’re doing at every single moment because you’d have to be watching a large number of people, blah, blah, blah, and access to the grassy area was cut off for weeks on end and the detainees got very, very upset about it. There were all sorts of reasons being given, the grassy area was too muddy or it was too cold or, you know, I mean as if these adults can’t decide whether it’s too cold to be outside or not, I mean, you know, it was obvious that it was inconvenient for the guards and they didn’t like it, so in terms of physical activity there was very, very little. Now I believe in Port Hedland they used to be taken to the local swimming pool sometimes, so it must vary from detention centre to detention centre. I have absolutely no idea what’s available in Baxter.

MS SANGSTER And were there children detained there?

DR FLESCH There were indeed children in detention and they were in for quite considerable lengths of time. Now some of them, there were children who were brought down from Nauru for medical treatment. There were also children who were simply the children who had fled with their parents. There would be a considerable fight to get them into schools

MS SANGSTER Would the people – some of the people that you visited did they have children and – – –

DR FLESCH Yes.

MS SANGSTER – – – in detention?

DR FLESCH Yes. Well that family that I was talking about, yes.

MS SANGSTER What about split up families? Were there families that had – – –

DR FLESCH Certainly. There was a woman that I used to write to when she was in Port Hedland and the letters suddenly stopped. She and her husband and two boys were all in detention in Port Hedland and the letters suddenly stopped and it wasn’t until one day when, I’ve forgotten why – that’s right, the detention visiting centre hours had changed and she wasn’t going to be able to bring the children – sorry, I’m telling this the wrong way around. What happened was the whole family was in Port Hedland, and it doesn’t matter how I found out eventually that they were in Maribyrnong, but they wound up with the husband in Maribyrnong and the woman and the two children living outside, and she used to come in and visit him every single day, the two boys would be at school, and she would come and visit him every single day and stay for the entire day, just going away when the centre closed at lunchtime, she’d walk across the road to Highpoint presumably and get herself some lunch, but the only time the boys could see their father was at the weekends and there was one time when, I’ve forgotten why for some reason she wasn’t going to be able to get a bus and so she was appealing to know whether anybody lived around her area could give her a lift, and it was only when I said, “I will try to find out”, and she gave me her name and I said, “For heavens sake, haven’t you realised I’m Juliet. We’ve been writing to each other for so long”. It was really quite extraordinary. You know, so I met the boys that I’d run around trying to buy clothes for even when they were in Port Hedland.

MS SANGSTER So you used to provide – detainees would ask you specifically for things that they – – –

DR FLESCH Yes, it depended – so far we’ve really only talked about my relationship with people in Maribyrnong. I developed quite a strong relationship and it’s, you know, one of my – one of the ones that I regard as a continuing friend, with a guy who had originally been taken to Maribyrnong – to Port Hedland because his boat had wound up on Ashmore Reef, he was one of the Iranians who was then sent to Maribyrnong and he got sent back to Port Hedland and subsequently to Baxter and is now out on a Temporary Protection Visa – I don’t know what sort of visa he’s got but he’s been out for some time – anyway, when he was sent off to Port Hedland I kept in touch with him and in fact I used to telephone him at least once a week and he was extraordinary, he’s a man who’s been gaoled in Iran and tortured and in fact he was the man that Julian Burnside ran that perfectly appalling case which wound up with the, I think it was the High Court actually deciding that even if there was reason to believe that a person being sent back to his home country would be imprisoned, tortured and killed, as the law stood it was the duty of Australian Public Servants to effect that person’s removal from Australia, and so my friend was the guy this was being told about. My friend had brought out from Iran videos which actually show the torture taking place in Evan Prison, in fact Julian Burnside has talked about this, he has seen the tape, I thank God have not, in which you can see a distressed family group in a room and you can hear somebody reading something and there’s somebody strapped to a sort of gurney in the room, and you actually see that person’s eyes being put out, and so this guy smuggled that tape out. He by the way worked in a chemical plant in Iran, he’s not a journalist or anything, but he used to make a special point of reporting to me things that he felt should be more widely known about Port Hedland. I remember once when there was a disturbance in Port Hedland and he rang me and I said “For heavens sake, Arthur, where are you?” and he said, “I’m in my room”, which was very interesting because it meant he was using a mobile phone which they’re not supposed to have, and I said, “Fine, stay there, just stay in your room.” “No, no, no, I ring you because is disturbance and I go out, I try to take photograph.” And I’m, you know, “You’re not supposed to have a camera.” I said, “For God’s sake, Arthur, just stay in your room.” “No, no, no, I am journalist”. I said, “You’re not, you’re a chemical engineer, stay put.” Anyway, he obviously had a really strong feeling not only of justice and human rights and all the rest of it, but he saw himself as a sort of leader within the camp, and in fact in a very large sense I think he was, and he would ring me and say we need – you know, some people have been brought down from here or they’ve got no clothes, they need this, they need that and I used to go to it. I’m doing this as a commercial by the way

MS SANGSTER So, coming back to when he was on the mobile phone to you – – –

DR FLESCH M’mm.

MS SANGSTER – – – what was he describing as in – – –

DR FLESCH That particular time, look I honestly can’t remember, there were times when he would report that people in a different kind of uniform had suddenly entered the camp and were starting to separate people out. I very often got to hear quite early about people who had got up on the roof and were slashing themselves with razor blades. I mean much of that would then be reported in the media. An awful lot of it you couldn’t get the media in the slightest bit interested, but if you knew who it was you could then try and ring the person’s lawyer and say are you aware that your client is up on the roof slashing himself with a razor blade. So he would just be reporting on various occurrences within the camp, so and so is still on hunger strike and is very weak, you know, that sort of thing.

MS SANGSTER And then you would write, you wrote a lot of letters to detainees and there was – – –

DR FLESCH Yes, yes. Well, I mean with this guy when I sent his parcel I always used to write a letter as well, but I mean I used to talk to him. People on Nauru, yes, I at one stage was writing to, and I’m not one of the big Nauru correspondence, there are many other people who develop much closer relationships with much wider number of people on Nauru, Elaine and Jeff Smith on the Gold Coast particularly, but I think I’ve given you the names of a few other people who – in Melbourne who have been very sort of Nauru-based as it were, but I had about six people that I used to write to. Now some of those have now been released. At least two of them to my very considerable distress agreed to go home, you know, when the government was offering them $2,000 bribe to go back and was in fact cutting their rations and saying, “You are never going to be released” – you know – “it is perfectly safe for you to go back”, you know, “and you are going to spend the rest of your life on this island unless you agree to go back.” They agreed to go back and I really find this quite hard to talk about – I’ll say the end bit first of all which is I am quite convinced that if these guys were still alive they would have continued, they would’ve kept in touch with me. There is no reason for them to cut off contact and they had every reason to believe that I was prepared to go on helping them. One of them in particular that I’m remembering, and I’m still not going to name him because if he should happen to be alive it could still be dangerous I guess, he wrote to me in December to say that he just couldn’t bear it any longer and he’d signed and agreed to go home and he’d been told that he would be sent home within a month, and he said, “I’m writing to ask you because I am on Nauru for two years, I have only T-shirt and shorts and in my country in January it is cold.” He didn’t have any clothes and he had no reason to believe that the Australian Government would provide him with anything before they put him on the plane. So I got him a coat, I got him a jumper, I got him some trousers, I got him some shoes, I hoped to God they fitted him. He of course wrote back and said, yes, they did fit, but, you know, he would have said that anyway, and he was sent back to Afghanistan in the winter. One of the most shocking stories that Julian Burnside has ever been able to tell I think was, I don’t know whether you remember the story of young Hamad Sawa(?) who had been told that his refugee application had been rejected and who sat up in bed one night, just sat up with a great cry and fell back dead. Now, Nauru Government refused to conduct an autopsy, the Australian Government said it would not of course conduct an autopsy because Nauru was a sovereign country. His family in Afghanistan asked for his body to be repatriated so that he could be buried in Afghanistan and the Australian Government refused because it was too dangerous to send the body back. Now, they were sending live human beings back to Afghanistan, but it was too dangerous for us to send a dead body back. That – that I think has been one of the things that has really shocked me about this whole business is the way it has I think forever destroyed my respect for the government and it’s instrumentalities, and I say that as somebody who was a Commonwealth Public Servant for 13 years and I was proud to be a public servant, and I – I used to – now I’m not saying that like the people who say I work for the electricity company and I’m so excited about it, but I mean I used to say when people said what do you do, I used to say I’m a public servant and I used to feel quite proud of it, and when people talked about beaurocrats with that sneer on their faces I used to get quite angry and now I just I don’t know how any – I’m sure there are decent people in the Commonwealth Public Servant Service but I really find it difficult to believe in the common human decency of people in the Immigration Department, and that shocks me.

MS SANGSTER And there was someone else as well that you mentioned that went back and you also haven’t heard anything?

DR FLESCH Yes, he was actually not a Nauru guy, he was a Hazara, an Afghan Hazara, and he had worked in Shepparton as a butcher for four years and his Temporary Protection Visa ran out and he was re-detained while they reassessed his case, and in the end he just gave up, went back. Now he left me an email address and I emailed for ages, I’ve never heard from him. Nobody else that I know of has heard anything from him and, you know, I’m just convinced he’s dead. Because even if they – I mean what most of the Afghans who returned were quite obviously going to do was immediately flee to another country, but they knew that whatever else they did they were never, ever, ever going to come back to Australia, you know, they would get to Pakistan and then they would try to get to Canada or try to get to Britain, whatever, but not Australia.

MS SANGSTER Australia?

DR FLESCH No. But there’s no reason why he wouldn’t have been able to get in touch with me. I haven’t moved in that time.

MS SANGSTER So when you talk about – when we talked earlier about this sort of, the trauma of the initial visit and seeing these people and its shocking content, did over time that change or do you think – – –

DR FLESCH Now, the Immigration Minister will tell you that the Maribyrnong Detention Centre has changed and, yes, I can tell you it’s been tizzied up in various totally cosmetic ways. Does the trauma become any less? To some extent you just get used to it. You get used to the fact that after five years you will go and be confronted by the same sadistic bitch and you will hand over the same identity document and she will look you straight in the eye and say, “Have you ever been here before?” I saw her do that to somebody who had been in the Maribyrnong Detention Centre as a detainee for two years and he came back to visit one of his friends. Now, for these guys to come back and walk through those gates again, I mean they’re grey-faced and shaking when they do it. So for her to look him in the eye and say, “Have you been here before?” and he said, “For Heaven’s sake, Helen, I was a detainee here”, and she actually said, “I forget you as soon as you’ve gone and you all look the same to me.” Now, you know, so to some extent – now when I go there and someone says, “Have you been here before”, sometimes I just think it’s funny, sometimes I just stare at them until they go on to the next question. Sometimes it enrages me to the point where, you know, I’d like to bite their ankles. Sometimes whether the actual visit is traumatic depends a great deal on the state of the person that you go and see. I mean I have got friends now among the former detainees for whom I remember – I mean one of them I’m thinking of in particular and this was a man in his 40s and the first time I saw him, something particularly horrible had happened to him, and the first time I saw him all he did was cry and it’s a sort of funny memory in a way because we have – I have a very strict rule about visiting people. I don’t care if they’ve been brought up to believe that women are a totally inferior order of being, I don’t care what it’s like in their country. This is my country and they are going to learn to shake hands. So I walk in and I say, “Hello, my name is Juliet.” Now, to some of the young Afghan blokes this could be absolutely shocking, but they’ve got to learn it, but anyway, so I walked in with this particular man that I’m thinking of and I shook his hand, and as I say we went and sat outside and when he wasn’t smoking he was just weeping. It was just horrific, you know, and I was trying to sort of talk, calm him down a bit, and when I got up to go I held out my hand and held out his arms like that and I thought I don’t care what the protocol is. Now I, you know, hug and kiss anyone who hug and kisses me but, you know, at that stage it was just such a thing because I’m sure that wasn’t way he would treat an unmarried woman in Iran either but, you know, you just see it’s the sort of human thing. Now after that first visit the next few visits with that person were still very difficult, the rest of it, but he was in there for so long and I got to know him so well that sometimes we’d go in there and we’d just be – it would be – except for the very bizarre surroundings and the fact that guards feel entitled to come and interrupt at any moment, the social worker will suddenly be feeling, you know, obliged to emerge from her burrow and, you know, come and interrupt at any moment. It’s hard to make it feel like a normal social thing, but in your own interaction with them it can feel like a normal social visit, and one of the guys for example was a very great reader and could not read in English and I managed to get him some books in Farci. So we used to have animated discussions about Middlemarch and the Canterville Ghost, because I mean it was wonderful to have something, particularly since I’m a sports moron, you know, and so if they want to talk about the World Cup I would try really hard to remember who’d won or even who was playing, but as for actually discussing the game, well no I didn’t watch it and I wasn’t going to watch it because I didn’t see the point of watching it because I wouldn’t understand it. You know, it was great to have something else to talk about. So the trauma changes to some extent and it depends, but then somebody might – you have no way of knowing in advance whether it was going to be an easy visit or a hard visit because the detainees themselves are – they may get bad news from home, they may have – they may just have had a particularly bad night, they may be feeling physically sick, you know, it varies, and so sometimes you’d go in expecting a sort of nice easy visit and you’d come out feeling absolutely traumatised. So the trauma, and there’s a certain familiarity – – –

MS SANGSTER With that sense of the familiarity, with that sense of being – – –

DR FLESCH You know what the routine is going to be so nothing about that shocks you. You know, I mean sometimes I’ll go in, if I’m wearing this thing for example sometimes the metal detector will be set off and sometimes it won’t. Now, I no longer start panicking about what it is I’m going to have to take off. I just take the thing off and put it in the little basket so it goes through the X-ray to show it’s not a bomb, you know, whereas the first time I would have been panicking, you know, what’s wrong, what have I done wrong. So, yeah, it changes to some extent.

MS SANGSTER And the people that you kept in touch with now do they talk a lot about that time in their lives or is it once again that thing of preferring not to remember?

DR FLESCH Sometimes something can suddenly set it off. They – no, they don’t – they don’t generally want to talk very much about it and when they do it will tend to be because somebody else is in detention and they’re talking about that person, but sometimes if they’ve had a very traumatic time – well, for example that story I told you about the guy getting his pressure suit thrown on the floor, that came up in relation to something utterly different and I think I was talking about one of the centre staff and I said something along the lines of, but I didn’t get the feeling they were deliberately cruel, and he said “Oh yeah” and told me that story. Now, you know, so it’s a matter of, and I suppose for the ones who are making the greatest recovery it’s something that just becomes part of their life and they will tell you that just as if it seemed relevant they’d tell you an anecdote from their school days, and I hope that’s the way it works, but I know they will still have nightmares. I mean it’s for them in a way they’re just in a larger prison now, because the ones who – the ones who have permanent residency if they can bring their families out that’s one thing, but the ones who are permanently separated from their families it’s just a permanent prison and the detention is permanently with them, but, no, I try not to talk about it because I hope there are other things going on in their lives and it’s much easier to talk about the course they’re doing or the work they’re doing, marriage or whatever.

MS SANGSTER And you will continue this team, the detention centre – – –

DR FLESCH While there are refugees there, yes. There was a brief period at the beginning of this year when there actually were no refugees there. Having said that it’s a very difficult thing in some ways because the sort of borderline between asylum seeker and visa over-stayer is a very difficult one to work out, because for example there are often cases, I can think of one in particular, of a bloke from the Indian in the south – yes, from the subcontinent, I can’t honestly remember whether he was Indian or Pakistani, he was not Afghani – his family had sent him out as a student and the obvious intention was that he should not return. They’d managed to get him out before he really got into trouble and he then had overstayed his Visa, because I mean it’s very difficult, they get sent out with enough money to pay their fees but they often don’t have enough to live on so they’re trying to do the 20 hours work that they’re allowed to do. They can’t earn enough money to live on so they wind up doing more work. They wind up dropping out of their courses, they wind up being visa over-stayers, they wind up in Maribyrnong. Now, if they – they then apply for asylum because they have a genuine fear of persecution if they go back. That’s a very sort of, there’s a borderline case. However, the mere fact that somebody has claimed asylum does not in my view necessarily make them legitimate asylum seeker and I can give you a spectacularly, I think really bizarre example in Maribyrnong. There was a woman there a couple of years ago who was a Canadian. She was a white skinned blonde born in Halifax Novo Scotia. She had worked, lived and worked for ten years in Toronto. She had met a guy on the internet, an Australian guy, she had come out to be with him, the relationship had not worked. Now the way she told it, “He dumped me on Christmas Eve at the detention centre.” I actually don’t believe that because that’s not how it works. You actually – you don’t get detained by the detention centre staff, you get detained at the behest of the Immigration Department, but anyway she had overstayed her visa. Now, she must frankly be bonkers because what you would do if you were a white Canadian is you would go back to Canada and you would reapply for another visa and you would be permitted to come back. She stayed in detention and announced that she was applying for asylum. Now, I have yet to know on what basis apart from being a pain in the neck you could apply for asylum saying you were being persecuted by the authorities in Toronto. I mean it just made absolutely no sense whatsoever, and I can say the refugees in detention really resented her because she was completely English speaking so she could get on with the guards really well. She never had any trouble explaining what she wanted, whatever, and of course because she was a woman in detention half the well meaning Care Bears started visiting her, you know, because they were so concerned about her. When she was eventually repatriated she was first of all taken on a shopping expedition by the detention centre staff and permitted to buy things for the journey to the value of $500, and believe me that was our money, taxpayers money. She was then escorted with by a social worker, not a detention – not a correctional services person, a social worker to Canada where she was handed over to another social worker. You compare that to sending somebody from Nauru in January in shorts and thongs, you know, it’s just extraordinary. Now as far as I was concerned that woman should have been – there was no reason to hold her for any length of time, she should simply have been sent straight back to Canada, and if she was going to play games like that she frankly should not have been allowed to return to Australia unless she had a return ticket in her pocket. I mean it was an outrageous waste of taxpayer’s money and she as an asylum seeker is somebody I would not be prepared to visit. But now I think, well last week there were I think two asylum seekers in Maribyrnong, possibly only one, the other people were all visa over-stayers or criminals, and the criminals I will not visit.

MS SANGSTER So there’s that sort of distinction there between – – –

DR FLESCH Yeah, but there’s no distinction made in the way they’re housed. I mean that’s a distinction in my mind and that’s the thing that I mean a great many of the detainees found deeply shocking. In fact there was something in the papers I think about – it wasn’t at Maribyrnong as I recall, and I think – wasn’t it at Villawood where there was somebody who’d actually been convicted of rape who was being held at Villawood and I mean Villawood’s got quite a large number of families there and there was a considerable feeling of outrage on the part of the asylum seekers, and I mean the people that I used to visit used to – “We are not criminal, we are housed with criminal, we are innocent.” You know, that’s the thing, they know they are innocent. Sorry, I’m repeating myself.

MS SANGSTER No, no, but the Australian Government doesn’t seem to make that – – –

DR FLESCH Well if you’re called an illegal then you’re not regarded as innocent, are you? I mean unless you are guilty of illegality, which is the most outrageous thing.

MS SANGSTER Is there any message that you would like to give to the Australian public?

DR FLESCH To the Australian public – I was going to say to the detainees, to the asylum seekers, it would be hang in there – to the Australian public, yes. What this government has been doing for the last ten years has besmirched Australia’s international reputation, it has betrayed the basic decency of the Australian people and it has traumatised innocent men, women and children in a way which is going to take a very long time to fix and a very long time to live down. Many of us felt when we heard about the stolen generations we thought, we felt guilty even if not actually responsible, but we felt we didn’t know. Well I don’t think anybody has the excuse now of saying they didn’t know about the treatment of refugees, and if we know about it we have an absolute duty to speak up and work for change.

MS SANGSTER Thanks.

DR FLESCH It sounds very self satisfied, but I mean it.

MS SANGSTER Thank you.

DR FLESCH Thank you.